This story appeared in the December 2015 issue of The Bulletin of the Golf Heritage Society.

By Pete Trenham

www.trenhamgolfhistory.org

Ted Smith was born in Philadelphia 1906, the son of immigrant parents who had come to the United States from Hungary and Americanized their name to Smith. His family moved to Chicago and at the age of 12 he requested clubs for Christmas because he had seen a picture of John D. Rockefeller playing golf. He began to play golf, caddy and hang around the golf shop at a public course. He asked the pro so many questions about how to make clubs he was nicknamed “questionnaire”.

At the age of 18 he went to work at the Seaview Golf Club as an apprentice club maker under professionals Jack Croke and Jack Schmidt. After stints working as a club maker and professional in Illinois and California he became a salesman for the MacGregor Golf Company, which was based in Dayton, Ohio. Ted covered the states east of the Mississippi River calling on the golf pros and Toney Penna covered everything west of the Mississippi.

Ted and Toney Penna soon convinced the managers of the MacGregor Company that they could make better clubs than what they were being given to sell. Ted and Toney moved into the MacGregor factory where Smith designed the irons and putters while Penna created the woods. The company began turning out the finest golf equipment in the United States and most of the top players like Ben Hogan, Byron Nelson, Jimmy Demaret and Tommy Armour joined the MacGregor staff.

Smith designed the Tommy Armour Silver Scot irons and putters, which became the “state of the art for golf clubs”. They were collector’s items 60 years later (as were Penna’s wood clubs). Smith was made superintendent of the MacGregor factory and Penna played the PGA Tour, returning on occasion to design a new driver.

When World War II broke out, the MacGregor factory was taken over by the government to manufacture things for the defense of the country. Smith made dummies used in testing experimental ejection seats for fighter planes. The government became aware of Smith’s talents and sent him to Camden, N.J. to work on the Navy supply ships. Smith created a new type of propeller for the ships that made them more efficient thus transporting the supplies to Europe more quickly. The Navy then asked him to find a way to protect its pilots who had been shot down. He helped design a jacket that contained foil, which made it more difficult for the Japanese to locate them on their radar, which was inferior to the United States Navy’s radar. This gave our Navy more time to rescue them.

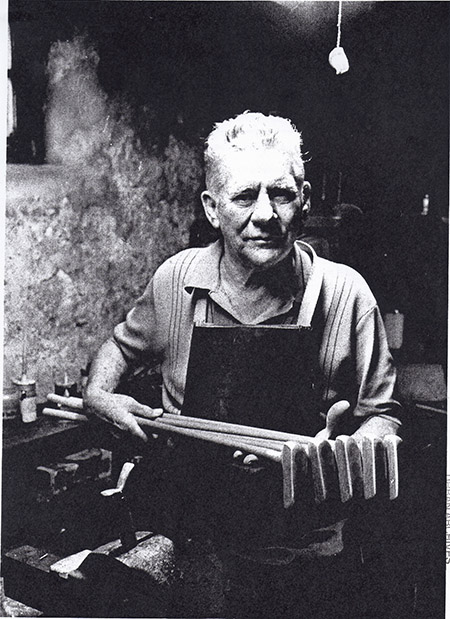

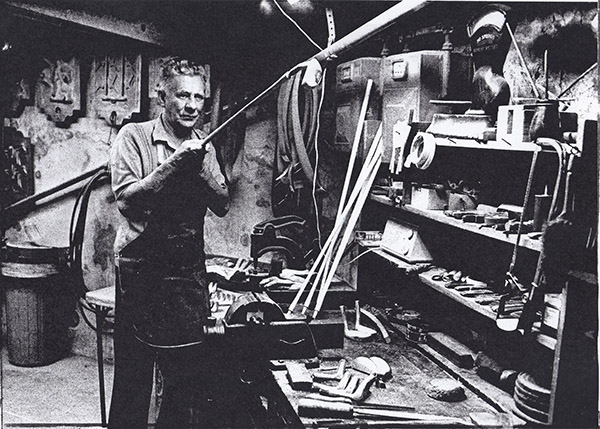

After the war Smith decided to stay in the Philadelphia area and opened the Ted Smith Golf Club Company at 8515 West Chester Pike in Upper Darby. He worked out of the basement of his home making the Ted Smith putters. His shop wasn’t set up for visiting customers. One had to enter from the outside through ground level pull-up doors and then descend a steep set of concrete steps. Without any employees except two high school boys who worked on Saturdays, he turned out about 2,000 putters a year, half wooden shafted and half steel. Eventually he had 30 different models for sale, which he designed himself.

Just one year after Smith started his business, Lew Worsham used one of Smith’s hickory shafted mallet head putters to hole the winning putt at the 1947 U.S. Open.

When Smith opened his business in 1946 (right after the war) there was a pent up demand for domestic goods like automobiles, which used steel. The big golf companies were buying all of the steel shaves that were available so Smith put hickory shaves in his putters. As it turned out the hickory shafted putters were very popular even though they were more expensive due to it taking longer to make one. It took him about two hours to make a wooden shafted putter and half as long to make one with a steel shaft. Smith said that he thought the hickory-shafted putters sold better because they had a feel that the golfers liked.

Each winter Smith and his wife would drive south selling the putters along the way until they reached South Florida. They would winter in Key West and a few months later they would head north selling the rest of the putters and taking orders for the new golf season.

In one of those ironies of life, the Japanese people who Ted had helped to defeat in World War II became his biggest and best customers. With the World Amateur Team Championship being played at Merion Golf Club in 1960, Ted put 50 of his hickory-shafted putters in Fred Austin’s golf shop on consignment. Each member of the Japanese team bought one of his putters. One member of the Japanese team who was affiliated with an import/export firm in Japan began importing Smith’s putters. By 1971, 60 percent of his putter sales were in Japan and he could have sold his total output there. With each order came a letter of credit and three days after the putters were shipped, Smith was paid by a local bank.

Smith had never advertised and now he wasn’t even making his occasional calls on the local pros. He said that the only reason that he continued to sell putters in the United States was to let the people know that he was still making putters in case his business cooled off in Japan. For over 30 years every Philadelphia pro shop stocked at least a few Ted Smith putters and each year most of them sold. When Smith sold his company in the late 1970s it was one more exodus from the golf business of a dying breed, the skilled craftsman who turned out hand made golf clubs.