Dr. Michael Hurdzan

Dr. Michael Hurdzan’s collection of golf maps, charts, blueprints and other achitectural drawings is quite extraordinary. The article in The Golf refers to Desmond Muirhead, a golf architect with a memorable personality and methodology. Click here to read more about this talented architect.

Col. Dick Johns

Col. Dick Johns has had a distinguished career in the military and in civilian service. He was honored recently with the Citizen of the Year Award, bestowed by the Middle Atlantic Section of the PGA. The brief article in The Golf could not do justice to Col. John’s career. Click here to see the full account of Col. Johns’ illustrious career.

Henry Cotton on the use of steel shafts

In his book, Golf (1931), Cotton mentions steel but emphasizes hickory shafted clubs and talks about purchasing and playing with the “named” clubs, such as the mashie, jigger, mashie niblick, etc.

By 1933 he had published Hints on Play With Steel Shafts published by British Steel Golf Shafts, Liverpool, Eng. From the foreword: “Anything that will simplify golf has an instant appeal to me, and therefore on every score, and on my own experience, I recommend players anxious to improve their game, not only to follow my example and change to steel shafts, but to see to it that every club in their bag matches every other one. In other words to play, not with a ‘collection’ of clubs, but with a set, thereby reducing potential errors to a minimum and making the possibilities of enjoying the game very much greater. I have endeavoured, therefore, not only to explain quite simply how to improve actual stroke play, but also to show how and why steel shafts have been of benefit and help to me.”

From Hints on Play with Steel Shafts, by Henry Cotton

Why I Changed to Steel Shafts

“It is still only a short time since I decided I could not find equals to my old hickory shafted clubs, with which I had built up my game (such as it is) and with which I had practised all my life.

“This not meant to give that impression that I had not tried steel shafts, but rather that I had not found an efficient substitute in steel shafts for my original hickory ones.

“As various new steel shafts came on the market I tried them out carefully, but could not convince myself that they were exactly what I wanted, so I waited and played with my hickory clubs.

“I felt, all the time, I was missing something; I wanted a shaft that was stiff but which had the whip in the right place. An easy feeling to have but it was long time before the shaft I wanted appeared, then the True Temper Master step-down shafts completely won me over. I tried them out at first with badly made heads which were too light or too heavy, or the wrong shape, etc., and it was some time before I found how really near they came to my hickory shafts.

“When I had the correct balance and right heads, I discovered that they possessed also many virtues which my hickory shafts had never possessed. I found, too, that with these shafts I had scarcely any jar, and even the occasionally half hit shot seemed to lose its sting before it reached the grip.

“I am still trying out various weights, thicknesses of blade, varous metals in the heads, in my endeavour to find the ideal combination (of the strength of the shaft and the weight and length) to suit my game. Naturally my experiments are within the stiffer range of the ‘Master’ shaft, as the medium and whippy grades do not suite my particular style, although they are eminently suitable for many other players.”

Cotton goes on to say that at the 1933 Open at St. Andrews “nearly all the competitors used steel shafts.”

John Duncan Dunn

Click here to see a PDF of Dunn’s article on American vs. British Clubs, published in the May 1902 edition of Golf, the USGA Bulletin. Richard McDonough, author of the Dunn article in The Golf, wrote: “This is a fascinating description of the shortcomings of the British clubmakers and their reluctance to adopt new techniques. Highly critical. It probably explains why he (Dunn) returned to London in 1904 to create his new company, undoubtedly utilizing the manufacturing techniques that he had employed in the U.S. and which are described in the article.

Full Q&A by Peter Yagi with author Keith Cutten on his book The Evolution of Golf Course Design.

Q. How did you come up with the idea for the book?

A. The research for the book actually started as a thesis, a requirement in my pursuit of a Master of Landscape Architecture degree from the University of Guelph. After the major years of construction at Cabot Links in Inverness, and having worked with Rod Whitman since 2007 at Sagebrush, I decided to return to school as a mature student in 2012. The recession had made me realize that the golf industry, specifically the profession of golf course design, was getting smaller and more competitive. I wanted to do something to set myself apart.

However, I did not start the thesis process with the intent of turning the results into a book. Instead, my research was simply the product of trying to answer my own questions as they pertained to the history of golf course architecture. In fact, and also commencing in 2012, it was the renovation of Pinehurst No. 2 which started the ball rolling.

After hearing Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw declare that they were ‘not environmental crusaders’ but simply wished to ‘restore the classic course to its intended design’, I began to ask myself how these changes could have been allowed to occur to such a masterpiece. Further, while sitting in a first year history course, I began to process the many events and external influences which would shape the top practitioners and history of landscape architecture. To me, having also taken similar courses in my undergrad in Planning and Environmental Design, the connections were both fascinating and revealing. Moreover, I was quick to realise that this method of study would be essential to our later success as landscape architects. As such, I began to ask myself why the study of golf course architecture had not been undertaking in such a manner.

Following a detailed review of the literature of golf course architecture, a journey which really started for me at the age of fourteen, I set to work to fill in the blanks. I decided to look at each designer with fresh eyes. Instead of fixating on their ultimate design philosophies and portfolio of work, I aimed to distill their influences and development as an artist. The effects of world history, economics, prevailing artistic trends, social movements, and the inter-personal relationships were illuminated and contrasted to reveal a more complete history. The resulting chronology and profiles revealed a deeper understanding of the profession. An understanding which I believe has made me a better architect in this age of renovations.

Because I needed to submit my research to a committee comprised of landscape architects, my thesis had been written in a manner which was accessible to even the golf architecture novice. So, when my degree was complete, I began to wonder if the golf industry would enjoy my findings. After contacting my friend Paul Daley, the Australian writer, editor and publisher, we soon decided it was a worthy project. We would spend the better part of the next two years polishing my research into The Evolution of Golf Course Design

Q. How long did it take to write and put together? (its really comprehensive!)

A. Including the writing of my thesis, the whole process took almost five years to complete. However, my research and understanding of golf course architecture would start much earlier.

Q. How did you find and obtain all the old photos and plans?

A. I spent more than three months, pouring over thousands of images and plans, in an effort to select those which would bring the words of the book to life. Both Paul Daley and I are truly proud of the book, and the initial feedback from people has been incredible.

Due to the support of people like Dale Concannon, Jon Cavalier, Evan Schiller, Gary Lisbon, Simon Haines and Ron Whitten, we were able to secure some spectacular imagery, spanning some 250 years. I also scoured the archives in Guelph (Stanley Thompson), North Carolina (Tufts) and Massachusetts (Frederick Law Olmsted) to source some incredible plans. In total, the book has more than 300 images and plans, showcasing architectural efforts from all over the world.

Q. What stands out as something interesting you learned while writing the book?

A. Though this period stretches for more than a decade, the importance of the work done by those operating between 1900 and 1914 (the onset of WWI) has frequently been undervalued when compared to the inter-war period (the Golden Age of Golf Course Design). After all, golf architecture as a profession was established in Britain. The decimation of the British economy and population following WWI prompted the movement of many to North America. Golf architecture’s pre-war practitioners made the move in an effort to exploit the budding markets across the Atlantic. However, the accomplishments achieved prior to the great wars set standards which last to this day. Further, it was the relationships between those challenging the conventions of the day which would change the industry.

In 1898, Horace G Hutchinson was instrumental in establishing The Oxford and Cambridge Golfing Society, commonly referred to as The Society. Interestingly, Hutchinson served as its first president, while John Low, his good friend, filled the role of captain. Arthur Croome was secretary, with Harry Colt a committee member. Bernard Darwin played in the first match, following The Society’s establishment. These relationships, formed between Hutchinson and the other members of The Society, have been largely taken for granted in the history of golf course architecture. In fact, these men took their relationships to the R&A, serving on multiple committees.

Moreover, the impact that Low, Colt and Darwin made on golf course architecture in the 1900s cannot be understated. Low’s efforts at Woking, Colt at Sunningdale, and Darwin with his pen, all worked to further the profession and deepen our understanding of golf course architecture.

If I am every crazy enough to write another book, I would love to devote more time into exploring this important era.

Q. What writing/publishing experience have you had in the past?

A. The Evolution of Golf Course Design is my first book. Additionally, I have penned several articles on the subject of golf course design over the past 12 years. While it would seem like a rather large jump to go from 1,000 to 2,000 word articles, to that of a book with more than 100,000 words, my background as a planner and landscape architect had already prepared me for such an undertaking.

As golf course architecture is largely a seasonal job here in Canada, I would frequently use this winter ‘down time’ to secure jobs at various multidisciplinary engineering and planning firms. The large reports and planning documents which I prepared during this time frequently exceeded 200,000 words. Further, these public documents (which needed to be detailed yet accessible) frequently incorporated research spanning some 10 to 15 years, from many different sources. It is funny how our past experiences can prepare us for something uniquely different!

Q. Who is your favorite architect and why?

A. Being a Canadian, and having started my career on the maintenance crew at one of his incredible courses, the obvious answer would be Mr. Stanley Thompson. His layout at Capilano, Jasper, Banff, St. George’s, Westmount, and Highlands have inspired me greatly over the years. Further, his writings and plans held at the University of Guelph have done much to influence my own ideas on golf course design.

Q. Who is your favorite golf writer/book on architecture?

A. As a student of the literature of golf course architecture, I have always loved the eloquent prose of Mr. Bernard Darwin. His writing style and breadth of work easily make him one of the most important figures in the history of golf literature.

On the other end of the literary output scale was a Mr. Robert Hunter. Yet, his book simply titled The Links did much to captivate me as a young man.

Finally, as a golf course architect, I have always loved the elegance of MacKenzie’s writings on the subject of golf course design. He often sighted the need for the designer to use their brains as their most valuable tool, saving a project both time and money. However, he also related this analogy to the site itself, and a designer’s ability to work with the land.

Q. Closing thoughts?

A. Just like great architecture “challenges the elite player, but encourages the beginner,” I took this same line when crafting Evolution. Though there is deep and rich historical information presented in the book to expand the mind of even the most well-read historian, the book is also presented in a manner that allows even the novice to access to this very important information. Accessibility was a major goal.

Early Golf in America…

…the USGA story by Maggie Lagle, offered several references that might prove valuable for those interested in further reading. They are listed below:

- North and South Carolina and Georgia Almanac 1788

- The Carolina Lowcountry Birthplace of American Golf 1786, by Charles Price

- The History of Golf in South Carolina in the Late 18th Century, by George C. Rogers Jr.

- The Reorganization of the South Carolina Golf Club, by Charles E. Fraser

- Commemorating the Heritage of Golf, by E. Harris Corbitt

- Newspapers: The City Gazette (Charleston) and The Georgia Gazette (Savannah)

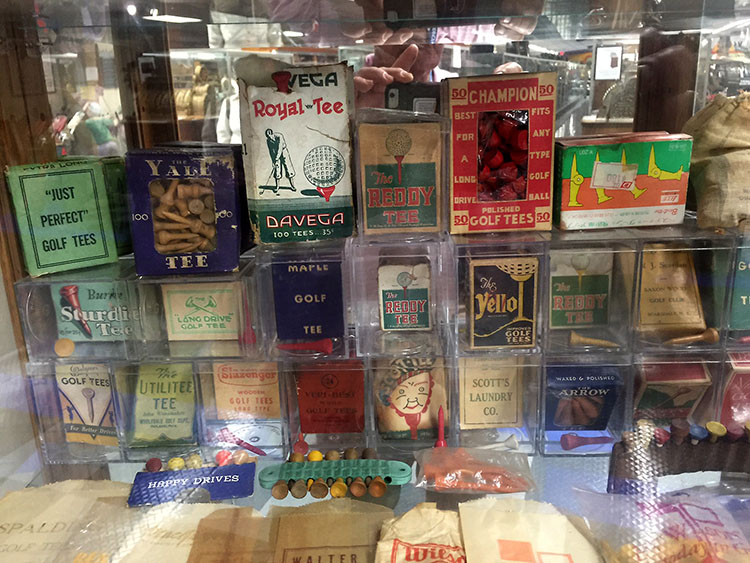

Tallahassee Automobile Museum (and golf)

Here are additional photos that could not be printed in the magazine due to space restrictions.