Book Review

The Bulletin, September 2017, No. 212

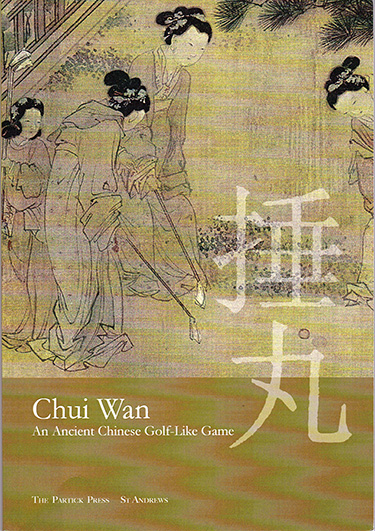

Chui Wan – An Ancient Chinese Golf-Like Game

By Anthony Butler, David Hamilton, and John Moffett

2016, The Patrick Press, St. Andrews

$23-27 on Amazon, ISBN 978-0-9510009-5-3

Review by Jim Davis

Bored shepherds wandering foggy linksland knocking rocks into rabbit holes with their crooks. While no one (except perhaps Seamus MacDuff ala Michael Murphy), knows for sure, this romantic image of golf’s origins, solidly Anglo Saxon, with a little Kolf from the Dutch thrown into the mix, generally passes for a likely scenario.

Thanks to researchers/authors such as Geert and Sara Nils and others, we know much more about stick-and-ball games common to European cultures. As well, there are reports of “paganica” played by Romans, and a drawing from a book on the Charles Darwin voyage of a young Chilean with stick poised on high to strike a ball.

With all these sticks and balls flying around the globe, surely the refined gentry in Asia had their game, too? Certainement.

Authors Anthony Butler, David Hamilton, and John Moffett have a look for us in their 2016 book, Chui Wan – An Ancient Chinese Golf-Like Game. What is it? How was it played? When did it exist? Was it a forerunner to modern golf?

These questions are addressed in a scholarly manner, though never heavily so. It is an imminently readable book, oddly familiar despite the intrinsically foreign subject. After all, one does not associate the ancient Chinese with golf and any hint of evolution from one to the other piques our interest.

It appears that chui wan was played on a field of from 20 to 40 yards, and often to a single target, repeatedly. Holes were dug, flags placed. It was a gambling game, report the authors, though low stakes were encouraged “to avoid penury.” Tokens are won and lost depending on strokes taken. There were singles matches and competitive play with up to 10 players in complex team formats. Often, the first to hole out wins and the others cease to play. It was a game played by the aristocracy, not by artisans.

Wooden balls were used and a variety of clubs with heads and shafts of wood for ground shots, lofting, and even evading a “stymie.” There was even a mysterious shot played from a squatting position.

An early painting from the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) shows the Emperor Xuanzong playing in a court setting. Holes are marked with flags and it reminds the modern golfer of a simple putting course. Evidently, there were several ways to play the game.

The Wan Jing, a book of 32 rules, interspersed with revealing commentary, was compiled in an attempt to standardize or capture the prevailing methods of play at the time. These rules were laboriously translated by modern Chinese scholars Chuan Gao and Wuzong Zhou and are printed in full at the rear of the book.

Most promote gentlemanly behavior and punish cheating. Gambling appears to have been a sporting trait among the Chinese and figures large in the rules. Of course, as money was involved, ejection from the game, and even “banishment,” were penalties for serious infractions. Literary types were considered excellent playing companions.

The authors address the similarities of chui wan rules with the Scottish game, but it appears that, in the main, they are common to any of several games involving sticks and balls arising in disparate cultures throughout the globe.

Noting that an examination of a culture’s rules for sport may offer insights into the attitudes of that society, the authors discuss parallels between the Analects of Confucius and the rules in the Wan Jing. Two examples:

Rule 7 – …make friends with the gentlemen and stay far away from the villains.

Analect 16.4 – It is beneficial to make friends with the upright, to make friends with the sincere…”

and

Rule 29 – If you are winning from an early stage, you must not become conceited. Conceit will certainly lead to failure.

Analect 13.26 – The gentleman is dignified but not arrogant.

Any conclusion that chui wan might have had an impact on the Scottish long game we call golf, must be “tentative,” the authors say. Too little is known about chui wan itself and its likely method of dissemination to Europe too tenuous to make any direct conclusion.

What is most striking, however, are the similarities between the old Anglo Saxon game and the ancient Asian pastime, arising in two disparate cultures far removed from one another. And those rules! – as complex and obtuse in ancient China as their modern R&A and USGA counterparts, but a great deal more fun to read in the Wan Jing:

Rule 30 – Honourable people have nothing to prove and play in a pleasant way. Harmony without conformity is the ideal. To win by the use of servility and flattery is not honourable.

This book will interest anyone curious about the nature of golf and of the, apparently, universal nature of man to apply stick to ball for amusement and profit. The authors are excellent guides in this cultural journey, thorough in their examinations, cautious in their conclusions, and compelling in their presentation.