Black History month 2022 – honoring early black golfers

By Jim Davis

In his book, Uneven Lies, The Heroic Story of African-Americans in Golf (2000, The American Golfer), author Pete McDaniel has a chapter titled “The Shadow People,” about the experience of Black Americans in the early golf industry in the U.S. It is a story of racial injustice as well as the poverty and indignity imposed by that injustice.

For many African-Americans, young men mostly, an escape of sorts was offered by service jobs and the growing status of country clubs in the country offered a measure of opportunity. The work was clean, it was honest and it brought its own satisfactions, at least when the employer had a sense of decency.

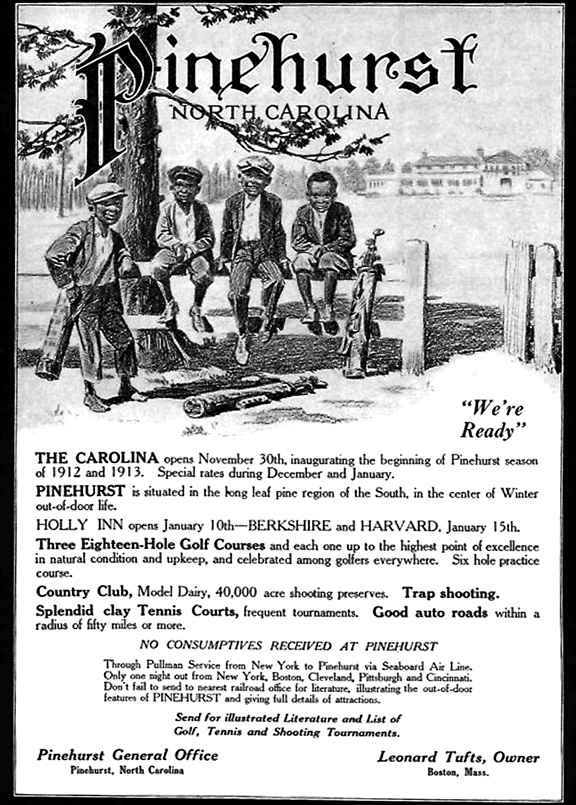

Life for caddies at the Pinehurst Resort may form a common picture for elsewhere in the country. Life could be hard – often carrying two bags for 54 holes over hilly terrain, for the 1916 rate of 50 cents for 18 holes, 70 cents for two bags. “Hard labor and hard times,” McDaniel wrote.

In a 2014 article for The Pilot (Pinehurst) author Lee Pace, in a quote from his book The Spirit of Pinehurst, talked with Willie McRae, another legendary Pinehurst caddy about just how much walking was involved. McRae worked for the Resort for 61 years, six days a week during the busy seasons. Pace said the math “is mind boggling.” Consider about 200 rounds a year, about 1,200 miles year, and it’s not a stretch to settle up at 72,000 miles for such a career. Said Pace, “That’s 15 round trips to Los Angeles.”

Click here to see The Pilot article.

James Walker Tufts, the Boston soda magnate who created the Resort as a winter haven for the wealthy, nailed it when he hired Donald Ross in 1901. The famous architect would stay for the next 48 years, along the way designing some 400 courses, many of which, especially his Pinehurst No. 2, would gain everlasting fame.

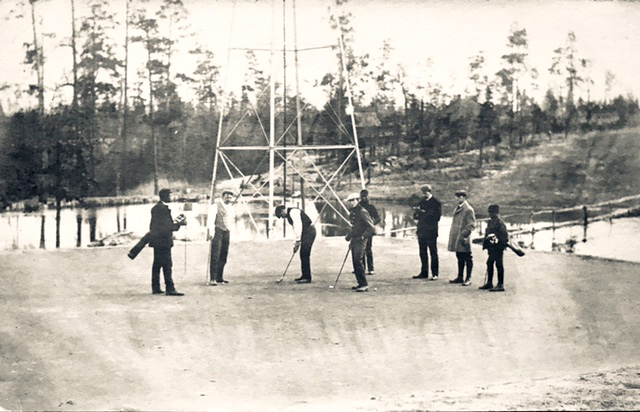

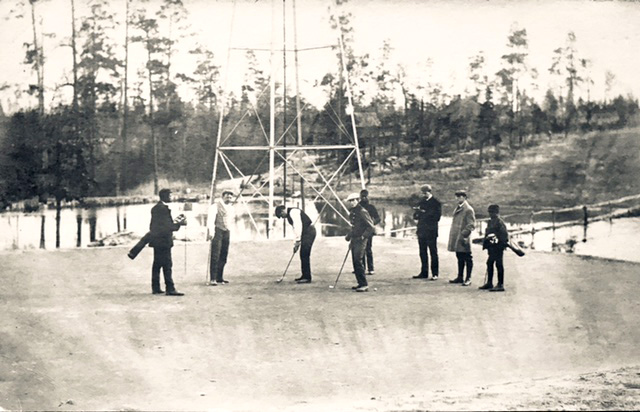

The Resort became a keen employer of local caddies, employing as many as 500 full- and part-timers before motorized carts came along in the 1950s and 60s.

One of the memorable caddies of the early days was Robert ‘Hard Rock’ Robinson, so-named by his father because he had an affinity for hard rock candy.

The young man, who wasn’t that fond of school, gravitated to the resort and found early work as a shag boy, retrieving practice balls. It wasn’t bad work and he liked being around the people of leisure, so to speak. Apparently he had an engaging personality which, added to his quick-study of the game and Pinehurst’s tricky greens, came to the notice of Ross who asked Robinson to become his personal caddy.

Robinson would later caddy for Ben Hogan and Sam Snead as well as other top golfers in the North & South Championship, a top event of that day.

In his book, McDaniel writes that Hard Rock, with his outgoing nature, got along fine with just about everybody and called Ross “…a Scotsman and a fair man.”

Eye trouble took its toll on Hard Rock and by the middle of the 1950s his caddying days were over. His retirement was that of many seniors who depended on Social Security and public assistance.

On the larger scene, the 1950s saw more people taking to golf in the period after World War II. President Dwight Eisenhower, an avid golfer, helped popularize the sport. But with the advent of the golf cart, caddies were in less demand. The Resort still offers caddie services on Pinehurst No. 2.

In an article for African American Golfers Digest (February 2016), former Pinehurst historian Paul Dunn wrote that in 1933 Pinehurst Caddy Master Donald A. Currie reported that even during the Great Depression the resort had as many as 190 caddies. According to Currie, “They went out twice a day, with some carrying two bags. On good days they made $3.00 plus tips, but the average was between 75 cents and a dollar daily.”

Dunn wrote that caddies were fed palatable food at a minimum cost. They were examined, vaccinated, given medical treatment annually and checked for contagious diseases. Apparently, according to Currie, some of the names on the caddy roster of the day included: George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, William McKinley, Martin Luther, Teddy Roosevelt, William H. Taft, Thomas Jefferson and Jesse James.

Click here to see Dunn’s article (co-authored by Debert Cook).

Caddies at Pinehurst, at least, got some much-deserved recognition in 2001 when the Pinehurst Resort & Country Club founded the Pinehurst Caddie Hall of Fame and installed its first class of 10, which included Jimmy Steed, Fletcher Gaines, Willie McRae, John T. Daniel, Jeff “Ratt Man” Ferguson, Teddy Marley, Robert “Hard Rock” Robinson, Hilton “Doctor” Rodgers, Robert Stafford and early-era caddiemaster Jack Williams.

In 2018, freelance writer Brian Mull wrote about a golf experience at Pinehurst with Jeff Ferguson on his bag. Ferguson at the time was the lone living member of the inaugural inductees for the Pinehurst Caddy Hall of Fame. Click here to see Mull’s article, written for The Caddie Network.

A news release about the event stated that “Over the last century and more, Pinehurst’s caddies have witnessed some of the greatest achievements and moments in all levels of golf. They have walked with the very best players ever to play the game, and they have been by the sides of the many guests and members who make this such a special place every day of the year.”

In an article published in June 1999 and updated for the U.S. Open in 2015, staff writer Jim Schlosser of the Greensboro News & Record, wrote about the local Sandhills village of Taylortown, which at its peak provided most of the men and boys who caddied at nearby Pinehurst. He talked with ‘Hard Rock’ Robinson who appeared, nattily attired, one day at the Resort, as well as another legendary Pinehurst looper, Jimmy Steed. Both have long memories about the players for whom they caddied. Steed, in particular, was less than impressed to have been paired with a then-unknown Sam Snead.

Click here to read Schlosser’s article.

Like the early days of golfing life for professionals, the early days for professional caddies offered meager earnings and recognition, but at least a sense of community within the sport they loved.