Sam Parks and the 1935 Open

By

John Fischer

© 2022

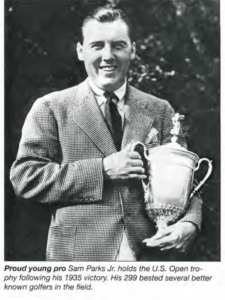

Ben Hogan once said the secret to golf “is in the dirt,” referring to hitting golf balls daily

for hours from the dirt of the practice tee. Sam Parks, the winner of the 1935 U.S. Open

at Oakmont Country Club outside Pittsburgh, also believed the secret to good golf lay in

the dirt, but in a much different way: study the dirt that comprised the course.

Parks was born in 1909 near Pittsburgh, and had a father, after whom he was named,

who was very interested in golf. Father Sam was a single digit handicap, at one time as

low as four, a director of the Western Pennsylvania Golf Association, and an

acknowledged expert on the Rules of Golf. He also belonged to Highland Country Club in

Pittsburgh where Gene Sarazen was the head professional.

In the spring of 1922 at the age of 12, young Sam took lessons from Sarazen, but in July

of that year Sarazen won the U.S. Open and was given the rest of the golf season off by

the club so he could cash in on his Open win by playing in exhibitions. Still, Sam got the

basics of his swing from Sarazen, who would later say (with tongue in cheek) that Sam

was his favorite student and had made him into the player who would win the U.S.

Open.

Parks had a slow backswing, a big turn of the shoulders and hips, then a sweeping

downswing swing with a lot of hand action, and a long flowing follow through. He

started with hickory shafted clubs but made the transition to steel, while retaining the

wristy hand action of hickory play.

Sam continued playing as a young man, but didn’t do anything spectacular as a junior

golfer. When he went to the University of Pittsburgh, though, he convinced the school to

start a golf team and became the captain. He established himself as a fine golfer in the

community.

Sam graduated from Pitt in 1931 and jobs were hard to come by. The depression had set

in and hit hard across the board. Sam thought that he’d have opportunities through

contacts his father had in the business world, only to realize that they had no openings

for him and, in fact, many of the contacts were themselves out of a job.

Then a position for a golf professional opened up at a small resort, the Summit Hotel and

Golf Club, near Uniontown about 45 miles south of Pittsburgh. It was a job and Sam

loved playing golf, so in 1932, with no real prior training for the position, Sam turned pro

and took the job.

A year or so later, a job opened at a nice club on the outskirts of Pittsburgh, South Hills

Country Club, and with some help through his father’s golf connections, Sam got the

position.

During the winter, Sam played the unofficial Western tour which started in California and

worked its way to Texas. Sam played well enough to get an invitation to play in the

inaugural Augusta National Invitation Tournament (now known as the Masters), where

he finished a respectful T-47, and then headed home to South Hills for the golf season to

give lessons and tend to the club membership.

While Sam didn’t win any of the tournaments on his swing through the west, he finished

high in a lot of events and was well known to his fellow competitors and to people who

followed golf closely, including Bob Jones who would become a good friend.

Sam came from a different background than most of his fellow tour players. Almost all of

them had started in the caddy ranks, worked as assistants in golf shops, repairing clubs

and learning the game. Sam came from a country club background, had taken lessons

from Gene Sarazen and had a degree in business from the University of Pittsburgh. Sam

was good company and got along with the others in spite of their different backgrounds

and was accepted as one of the guys.

As for big time golf, Sam had qualified for the U.S. Open in 1931 and 1932, but missed

the cut both times. He qualified again in 1933, but had to withdraw due to an injury

sustained in an automobile accident. Sam qualified for the Open in 1934 at Merion Golf

Club in Ardmore, Pa., just outside Philadelphia. Sam made the cut and finished T-37 with

a score of 309. However, the 1934 Open only paid the top 17 players, so Sam didn’t

make any money, but he felt that he’d done well enough to prove to himself he could do

well the following year when the Open was scheduled for Oakmont. He’d played

Oakmont on several occasions, including sectional qualifying rounds for the Open.

Oakmont was a course designed and built by Henry Clay Fownes (pronounced

“phones”), a Pittsburgh industrialist who loved the game of golf. Fownes played in

several U.S. Amateur Championships, and made the quarterfinals in 1903. His son,

William C. Fownes was also a fine golfer, winning the U.S. Amateur in 1910.

Henry Fownes wanted to built a golf course of his own. He had seen the gutta percha

golf ball disappear almost overnight after the introduction of the wound rubber core ball

which went farther than the old “gutty,” making many fine courses obsolete for major

tournament play. The new Fownes course was not to be overwhelmed; it would

measure at a monstrous 6400 yards when it opened in 1903, with room to lengthen the

course if necessary.

Fownes liked the style of British links courses: hard rolling fairways, few trees, and fast

greens with slopes, subtle rolls and false fronts. Oakmont was a challenge. Trees had to

be removed en mass and, unlike linksland which was porous and drained quickly, the

Oakmont site consisted of hard clay. Fownes had to design drainage trenches at the

bottom of slopes to draw the water away from fairways and greens, and the trenches

presented new hazards for the player who was off line.

To produce the fast greens that Fownes wanted, he had them cut to one sixteenth of an

inch, and then, for tournament play, had them rolled with a 750 pound roller. The greens

were fast, but true. But you had to know the line and hold to it. Sam Snead once

commented that the Oakmont greens were so fast that when he went to mark his ball,

his ball marker slid off the green. A frustrated Arnold Palmer said, “You can hit 72 greens

[in regulation] in the Open at Oakmont and not come close to winning.”

If the greens weren’t a problem always in the back of your mind as an Open competitor,

consider the thoughts on Oakmont’s starting holes made by a golf course architect:

“How about this for design variety? The first six holes: A long, downhill par-4, a short

uphill par-4, a medium uphill par-4, a getable par-5, a short par-4 and a short par-3. All

six holes vary in fairway width, green size, hazard presence, and preferred approach

angle. It is simply tough to beat.” In other words, the first six holes tested your entire

game.

There were 220 bunkers at Oakmont for the 1935 Open and they were treacherous. The

bunkers were filled with heavy sand from the Allegheny River, and the sand was raked,

not to smooth it out, but to make furrows. A special rake, weighted with a concrete slab

and having two inch triangular prongs, was used to make furrows two inches deep and

two inches apart. The only way out was to blast and hope. Many contestants complained

about the bunker style, but the younger Mr. Fownes responded, “A shot poorly played

should be a shot irrevocably lost.” And that was that.

Bob Jones had no love for the furrowed bunkers. He’d finished as runner up in the 1919

U.S. Amateur at Oakmont, but stayed silent about his distain for the style of the bunkers.

He thought his comments might sound like “sour grapes” from a loser. But after winning

the Amateur at Oakmont in 1925, Jones commented on what he saw as an unfairness.

Jones could play a chip, a cut shot or a blast from normal bunkers, but Oakmont made

everyone play a blast shot due to the deep furrows, removing an advantage for a skilled

bunker player.

As an aside, the furrows were removed for the 1953 Open scheduled for Oakmont

because several players threatened not to play if they remained. The USGA convinced

the Oakmont board to reduce the number of bunkers and do away with the furrows.

William Fownes had passed away in 1950, and no one put up a strenuous objection.

In 1935, the course was set out with a par of 72, 37 out and 35 in, with a total of 6981

yards, including the behemoth 12th hole, a 621 yard par-5, played by the members as a

par-6. Fairways also had slope and precision was necessary off the tee to be in the

correct position for the second shot, but given the length of the course, a long tee shot

was also required. And the cruel bunkers and voracious rough had to be avoided.

The course was a monster, and Sam Parks decided to understand it by playing nine holes

daily at Oakmont early each morning for about a month before the tournament, with

the approval of young Mr. Fownes. His playing partner was Emil (“Dutch”) Loeffler, the

head greens superintendent at Oakmont, and also the club’s head golf professional.

Loeffler was no slouch as a tournament golfer. He played in six U.S. Opens, finishing 10th

in 1921 and was a quarter finalist in the 1922 PGA Championship. Loeffler probably

knew more than anyone about Oakmont, strategy for playing the course and the many

quirks the course might suddenly throw at the unsuspecting golfer.

Parks and Loeffler didn’t always play nine holes in succession. They frequently skipped

around to play different holes, chip from various angles and study the green complexes.

Sam said that he learned in college that to remember things it was best to take notes,

and that’s what he did in those early morning outings with Loeffler. Sam didn’t measure

yardages, but he made notes on what club he played from various points on the course

such as a tree, a dip in the fairway or a bunker.

Parks also made charts of the greens, dividing them into quadrants and noting the break

and a special box showing the direction of the grain on the greens; some say grain

always breaks toward the setting sun, but that is incorrect. Grain isn’t heliotropic and

grows in any direction and, in many instances, grows in different directions on the same

green. Today, it’s not as much a factor with new strains of grass which grow vertically

and not on an angle.

Sam said that many of the good tournament players could play a course and remember

these points, but Sam knew he needed to write it down and refer to his notes during

play. Some credit the first yardage book to Deane Beman, others to Jack Nicklaus, but it

was Sam Parks who made the first such book, although he listed clubs hit from various

points instead of yardages. Unfortunately, Sam’s notes have not survived, although he

did chart out his shots on a course map for the last two rounds of the 1935 Open which

is in the archives of Oakmont Country Club.

Before the 1935 Open at Oakmont, Parks made his usual Western swing from California,

through the Southwest, with a stop in Augusta where he’d again received an invitation to

play in the Masters. This time around, Parks finished T-15, a great improvement from his

T-46 the prior year.

With his Western swing behind him and a good showing at the Masters, plus his daily

practice with Dutch Loeffler in the weeks prior to the Open, Parks felt he was ready to

make a good showing in front of a hometown gallery.

The format for the Open was 18 holes each on Thursday and Friday, when the field was

cut, and 36 holes on Saturday. In the first round, Sam came in with a 77, six strokes

behind the leader, Alvin Krueger, but in the middle of the pack. On Friday, the second

day of play, a tremendous gale came up, blowing across the almost treeless course,

knocking over scoreboards and almost bringing down the press tent.

Sam missed the worst of the storm, and posted a 73, tying the low score of the second

day, and putting him just four strokes behind the leader, Jimmy Thomson, known as the

“siege gun” because his long drives off the tee.

At the time, the USGA did not pair contestants by score with the leaders going off last;

that’s an invention of television. Leaders were mixed through the field which gave

galleries more of an opportunity to see the best players up close, and with the same

pairings for the last 36 holes, no one knew what was going happen. Saturday wasn’t

“moving day” to position yourself for the next day, it was the day.

Parks was paired Macdonald Smith who’d started the tournament with rounds of 74 and

82. Parks and Smith had starting times of 8:50 am and 12:50 pm, just four hours apart

which would include 18 holes of golf and barely time for a quick lunch before heading

out for the final 18.

The weather on Saturday continued with rain and wind. After 54 holes, Parks fired

another round of 73, was tied with Jimmy Thomson for the 54 hole lead, and began to

feel he might have a chance if he could just hold himself together for the last 18 holes.

But in addition to Parks, there were at least 10 other players with a good chance to win,

including such big names as Walter Hagen, Denny Shute, Gene Sarazen, Henry Picard,

Dick Metz and Al Espinosa.

At the start of the last round, Parks put together a solid 38 for the first nine holes, one

over par, but it was the streak he had playing one under par from the fifth to the 14th

hole that put Parks in position to win. Parks stumbled as he headed home with bogies at

the 15th, 16th and 18th holes for a 76 and a total of 299.

Jimmy Thomson fell apart and finished with a 78 for 301 to take second place.

But it was Walter Hagen who almost stole the show. He birdied the ninth and had to play

the last nine holes in even par to win or one over to tie. On Friday, Hagen had played the

second nine in 34, one under par. A crowd estimated at 10,000, rushed out to see what

the “Haig” could do. But Hagen just didn’t have his old magic and ended up at 302 in

sole third.

“All I know is this,” said Parks of his win. “I played all the golf I had in me. I was scared to

death down the stretch, but I tried to hang in with all I had.” It’s sometimes said that no

one wins the Open, it’s just that others fall away. Thomson faltered and finished second;

Hagen faltered and finished third; and Sarazen, Parks’ mentor, and winner of the Masters

just a few months earlier, faltered and finished T-6. But Parks didn’t falter.

The press, always looking for a “hook” or and angle for a story, could have made Sam a

Horatio Alger golfing hero who rose to the top by hard work. Instead, the press, led by

Bill Richardson of The New York Times and Grantland Rice, who wrote a daily column,

The Sportlight, which appeared in 100 newspapers, decided that Parks was a dark horse

who had come out of nowhere to win the Open. Some of the reporting seemed to be

pulling for Hagen to end his long career with an Open victory at Oakmont, but Hagen

couldn’t pull it off.

The dark horse characterization was probably unfair. Players on the winter tour knew

Sam’s abilities as a golfer, and the best odds you could get from bookies for Parks to win

the 1935 Open were 20-1. He was no long shot.

Did all Parks’ study of Oakmont bring victory? One indication is that Parks only three

putted twice over 72 holes on Oakmont’s treacherous greens, while the greens were

giving others fits.

Parks won $1,000 for his Open win and $1,509 for the year. It is also the most money he

won on tour in any one year. After his victory, Sam played a series of exhibitions with

runner up Jimmy Thomson, netting him $17,000, and also got a contract with Bristol Golf

for $100 a month to endorse their clubs.

The following year, as defending Open champion, he missed the cut, but played

respectfully afterwards in the Open through 1941. In the 1935 Ryder Cup Parks played

Alf Perry, the 1935 British Open champion, in a singles match. Parks and Perry halved

their match when Parks holed a 30-foot putt at the 36th hole.

In 1937, Parks quit playing the winter tour, but kept his club job. He did continue playing

in the Open as a former champion and the Masters. In 1942, Sam decided to leave

professional golf and take a sales position with U.S. Steel where a top salesman might

make $20,000 or more a year. Sam rose through the ranks at U.S. Steel and joined

Oakmont as a member in 1947. He kept playing good golf and, at age 50, tied the

Oakmont course record of 65. Parks retired from U.S. Steel in 1972 and moved to Florida

where he became a sales associate for condominiums at the Belleview Biltmore Hotel

and its two golf courses, which were owned by U.S. Steel.

Parks continued to play in the Masters as a past Open champion until 1963 when only

past Open champions from the last 10 years were invited to play. Sam then attended the

Masters as a non competing invitee mingling with his golfing friends from the past. He

passed away in 1997 at age 87.

Parks didn’t have a Hall of Fame record, but he demonstrated that hard work and

studying a course to understand its nuances can pay off. A tip of the hat to Sam, a good

guy who did well.