African‑American Contributions to Golf

Many African‑Americans made significant contributions to the game of golf from the late 19th century to the modern era as pioneers, innovators, and competitors. From John Shippen to Tiger Woods, from the United Golfers Association to the PGA Tour, in spite of racial roadblocks, Black Americans have shaped the history of golf in many ways. Here are a few of their remarkable stories.

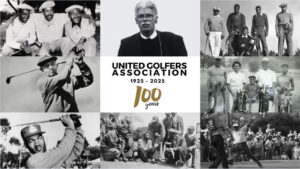

The United Golfers Association (UGA) celebrated its centennial last year. Created in 1925 to provide competitive opportunities for Black golfers excluded from white‑run tours. As summarized on its website, the UGA:

“[S]tands as a monumental testament to the African American community’s unwavering pursuit of equality and inclusion within the sport of golf. During a time of pervasive segregation and racial discrimination, the UGA emerged as a beacon of hope, providing Black golfers with a platform to compete, showcase their skills, and challenge the discriminatory practices that barred them from mainstream golf.”

The UGA organized national championships and regional tournaments that sustained elite competition during segregation. UGA events were also important cultural gatherings supported by Black communities and businesses. Players such as Ted Rhodes and Charlie Sifford developed their skills within its structure, proving that high‑level golf thrived outside mainstream recognition. Today, the USGA Museum and PGA historical initiatives increasingly highlight the UGA’s role in preserving competitive excellence during exclusionary decades.

From the UGA website

The organization’s legacy parallels that of baseball’s Negro Leagues, illustrating how marginalized athletes built parallel institutions to sustain their sport. Its influence remains visible in diversity initiatives and historical research programs that seek to integrate forgotten chapters into golf’s official narrative.

John Shippen Jr. (1879-1968) became the first African‑American professional golfer when he competed in the 1896 U.S. Open at Shinnecock Hills, finishing tied for fifth. Learning the game as a caddie, Shippen’s skill challenged assumptions about race in early American golf. The presence of Shippen and Shinnecock tribe member Oscar Bunn was protested by several competitors. However, USGA President Theodore Havemeyer defended their inclusion, insisting that talent would be the basis for competing in USGA championships, not race or ethnicity. Despite strong performances, Shippen was denied many opportunities available to white professionals and spent much of his career working as a teacher and clubmaker.

Shippen’s story demonstrates both the presence of early Black excellence and the structural barriers that limited recognition. In recent decades, the USGA has elevated Shippen’s legacy through museum exhibits and educational programming, positioning him as a foundational figure in the sport’s American history.

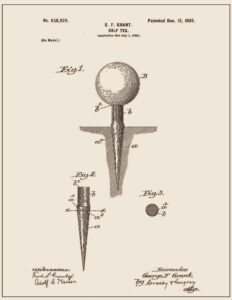

Dr. George Franklin Grant (1846-1910), a Harvard‑trained dentist and the university’s first African‑American faculty member, contributed to golf through innovation rather than competition. In 1899, he patented an early wooden golf tee designed to elevate the ball consistently while protecting course turf.

Prior to Grant’s invention, golfers often used sand mounds or improvised devices. Although he did not commercialize his design widely, his concept anticipated the modern tee used worldwide today. His work illustrates how Black inventors influenced the technological development of the sport even when recognition lagged behind. The USGA has since incorporated Grant’s patent into historical exhibits that explore equipment evolution, helping to restore his place in golf history. Grant’s legacy underscores that African‑American contributions to golf extend beyond playing achievements to foundational innovations that changed how the game is played.

Racial segregation also limited playing opportunities for Black golfers and several pioneering groups.

A dominant figure on the UGA circuit, Ted Rhodes (1910-1969) became one of the most influential figures in the fight to integrate professional golf. Known for powerful ball striking and competitive consistency, Rhodes won multiple UGA national titles and competed in several PGA‑sanctioned events despite ongoing barriers. His tie for fourth in the 1948 Los Angeles Open (now the Genesis Invitational) at Riviera Country Club once again demonstrated that Black professionals were capable of competing at elite levels. Further evidence came only weeks later — he was the first African American to compete in the U.S. Open (also at Riviera) since John Shippen in 1913. He recorded a 1-under-par 70 in the first round, leaving him three strokes out of the lead, but ultimately finished T51.

Ted Rhodes

Rhodes repeatedly challenged the PGA of America’s “Caucasian‑only” clause, helping apply pressure that ultimately led to policy change in 1961. While his achievements were often overlooked during his lifetime, modern historical research supported by the USGA has restored his prominence in golf’s narrative. Rhodes’ career symbolizes the persistence required to transform exclusion into opportunity. Read more on the GHS website in an article authored by Jim Davis: Easygoing Teddy Rhodes had a ‘passion for the game’

Bill Powell (1916-2009) responded to discrimination by building his own opportunity. In 1948, after being denied access to existing courses, he opened Clearview Golf Club in Canton, Ohio—the first course in the United States designed, built, owned, and operated by an African‑American. Powell financed construction with personal savings and family support, insisting that Clearview welcome players of every race. The course hosted UGA events and became a community hub that embodied inclusion long before it became industry policy. Powell’s perseverance transformed Clearview into both a business success and a civil rights symbol.

L to R: Billy Powell, Marcella Powell, Larry Powell, Bill Powell and Renee Powell, circa 1960.

The course is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and Powell received the PGA of America’s Distinguished Service Award. Today, the USGA and PGA highlight Clearview in museum displays and educational programs, recognizing it as a landmark in golf’s social history.

Other pioneers also created clubs and courses that provided playing opportunities for Black golfers. Shady Rest Country Club in Scotch Plains, New Jersey, occupies a unique place in American golf history as one of the nation’s earliest African-American–owned and operated golf facilities. The property that would become Shady Rest began as the original course of the Westfield Golf Club in the early 1900s. When Westfield, an all-white private club, relocated to a new site in the 1920s, its former course became available. Black investors and community leaders recognized a rare opportunity: they transformed the existing golf grounds into what became Shady Rest Country Club, creating a space where African-American golfers could play, socialize, and compete with dignity.

During segregation, the course maintained strong competitive connections to the United Golf Association and the Negro Golf Circuit, welcoming players who were denied entry to white-run tournaments. John Shippen Jr. worked at Shady Rest, further cementing its place in golf history as a training ground for Black professionals and amateurs seeking opportunities unavailable elsewhere. Today, Shady Rest stands as a symbol of resilience and transformation—a place where a course once shaped by exclusion became a powerful instrument for inclusion.

Langston Golf Course, Washington, D.C.

Opened in 1939, Langston Golf Course in Washington, D.C., became one of the most important public golf facilities for African‑Americans during segregation. Langston hosted UGA events and served as a gathering place for local players, reinforcing golf’s role within community life. Preservation efforts by residents and historians ensured the course survived redevelopment pressures decades later, cementing its status as a cultural landmark. Langston’s story demonstrates how public infrastructure helped expand participation alongside private initiatives like Clearview Golf Club.

The personal achievements of many Black golfers during the second half of the 1900s deserve recognition but several players truly stood out.

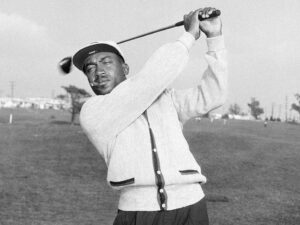

Charlie Sifford (1922–2015) is widely recognized as the player who permanently broke the PGA Tour’s color barrier. Before earning full tour membership in 1961, Sifford competed extensively on the United Golf Association circuit, where he developed a reputation for resilience and competitive toughness. Once on the PGA Tour, Sifford proved he belonged through performance as well as perseverance. He captured victories at the 1967 Greater Hartford Open and the 1969 Los Angeles Open, achievements that demonstrated African-American golfers could win against elite fields. Beyond individual titles, Sifford’s presence reshaped professional golf’s culture, encouraging governing bodies to reconsider long-standing exclusionary practices.

Charlie Sifford

Later in life, Sifford became a mentor to younger players, including Tiger Woods, who frequently acknowledged the path Sifford helped clear. Institutional recognition eventually followed decades after his competitive prime. He was inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame and received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2014, one of the nation’s highest civilian honors. Today, both the PGA of America and the USGA prominently feature Sifford’s story in museum exhibits and historical programming, presenting him not only as a successful competitor but as a transformative civil rights figure within golf.

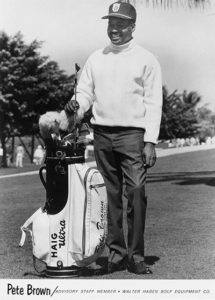

The first African‑American to win a PGA Tour event, Pete Brown (1935–2015) captured the 1964 Waco Turner Open. Brown’s win signaled that the barriers broken by earlier pioneers such as Ted Rhodes and Charlie Sifford were beginning to translate into tangible competitive success.

His breakthrough victory was followed by a second PGA Tour title at the 1970 Andy Williams-San Diego Open Invitational, reinforcing his reputation as a legitimate contender rather than a symbolic participant. Despite limited sponsorship opportunities and the pressures of competing in a still-evolving environment, Brown maintained a steady career during a transitional period for the sport.

The career of Lee Elder (1934–2021) bridged the gap between early integration and broader acceptance within professional golf. A four-time PGA Tour winner, Elder achieved consistent success through patience, course management, and mental toughness. His most historic moment came in 1975 when he became the first African-American invited to compete in the Masters Tournament at Augusta National, one of the sport’s most tradition-bound venues. Elder’s appearance at Augusta was far more than a personal milestone. It represented decades of advocacy by Black golfers seeking equal access to elite competitions. The pressure surrounding the event was immense, yet Elder approached the tournament with composure, understanding the symbolic importance of his presence. His participation helped accelerate conversations about inclusion at historically exclusive clubs across the country.

Lee Elder

In addition to his tremendous professional success, ending his career with four PGA Tour wins, eight Senior PGA Tour wins, and seven top-25 finishes in major championship, Elder managed the historic Langston Golf Course in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

In 2021, Elder took place in the traditional opening tee shot ceremony as an Honorary Starter at the Masters.

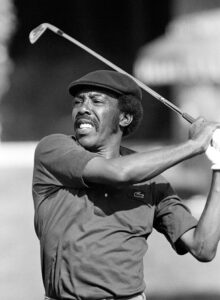

Calvin Peete

In the 1980s and 1990s, Calvin Peete (1943–2015) compiled a remarkable PGA Tour career, winning 12 events, including the 1985 Players Championship. He was a member of the U.S. Ryder Cup teams in 1983 and 1985. He became the most successful African American golfer in PGA Tour history, establishing a record that would be surpassed only by Tiger Woods.

His success demonstrated that accuracy could rival power in modern professional golf. Peete hit a staggering 84.55 percent of fairways in 87 PGA Tour rounds. In 1984, he won the PGA’s Vardon Trophy for the lowest scoring average. Peete remains one of the most statistically accomplished African‑American golfers in tour history, and his achievements are frequently highlighted in PGA Tour historical materials celebrating diversity milestones.

Althea Gibson (1927–2003), achieved fame as a tennis player, one of the first Black athletes to cross the color line of international tennis. who went on to win 11 Grand Slam titles: five singles, five doubles, and one mixed doubles. In 1957 and 1958, she was voted Female Athlete of the Year by the Associated Press.

After retiring from tennis, Gibson joined the LPGA Tour in 1964 as its first African‑American member. Her participation challenged both racial and gender barriers in professional golf. Though her competitive success was modest compared to her tennis career, Gibson’s presence broadened the sport’s cultural horizons and inspired future generations of Black women athletes.

GHS member Renee Powell (1946– ) occupies a distinctive place in golf history as both a pioneering competitor and an influential ambassador for inclusion in the sport. Born in 1946 in Canton, Ohio, Powell grew up at Clearview Golf Club, the course her father, Bill Powell, built to provide African-Americans access to the game during segregation. Powell became the second African-American woman to compete on the LPGA Tour, following Althea Gibson, and played professionally during the late 1960s and 1970s. Although tournament victories proved elusive, her presence on the tour represented a significant breakthrough at a time when few Black women were seen in professional golf.

Renee Powell with the Ohio historical marker honoring Clearview Golf Club

She is a member of 12 Halls of Fame. Other notable awards include being named PGA of America First Lady of Golf, the USGA Ike Grainger Award, the LPGA Pioneer Award, and the inaugural Charlie Sifford Award for advancing diversity in the game of golf. Other significant honors were extended by organizations in St. Andrews, Scotland, the “Home of Golf.” In 2008, Powell became the third American golfer (and the only woman), to receive an honorary doctorate from The University of St. Andrews. And in 2015, she became one of two American women given honorary membership into the Royal & Ancient Golf Club of St. Andrews.

Renee Powell’s legacy rests not only on her LPGA career but on decades of advocacy that helped reshape golf’s culture. Through youth programs and international outreach, she has continued Clearview Golf Club’s mission of access and education. Her work continues to inspire new generations of players while reminding the sport of the pioneers who expanded its boundaries.

And of course, Tiger Woods (1975– ). Woods’ career stands as one of the most consequential in the history of golf, not only for his competitive dominance but for what his success represented within the broader arc of African-American achievement in the sport. When Woods won the 1997 Masters Tournament by a record 12 strokes, becoming the youngest champion in tournament history, he did more than secure his first major title — he signaled a cultural shift in a game that had long excluded Black competitors from its highest stages.

Woods would go on to win 15 major championships and tie Sam Snead’s PGA Tour record with 82 career victories. His combination of power, precision, and psychological resilience redefined modern golf. The surge in television ratings, corporate sponsorship, and junior participation that followed — the “Tiger Effect” — reshaped the sport’s global profile.

Tiger Woods with his Majors hardware

Yet Woods’ ascent cannot be separated from the struggles of those who came before him. Charlie Sifford endured racial hostility to integrate the PGA Tour in 1961, dismantling the “Caucasian-only” clause that had formally barred Black players. Lee Elder, in 1975, became the first African-American to compete in the Masters, stepping onto Augusta National’s fairways under intense scrutiny and symbolic weight. Their perseverance created the structural openings that made Woods’ rise possible.

Woods inspired countless young golfers of color. His 2019 Masters victory, following years of injury and personal adversity, reaffirmed both his competitive greatness and enduring influence. In the long continuum from exclusion to excellence, Tiger Woods stands not as an isolated phenomenon, but as the most visible chapter in a story written by generations of African-American golfers who challenged the boundaries of the game.