THE “CROSBY CLAMBAKE”

On a stretch of coastline where cypress trees cling to rocky cliffs and the Pacific Ocean dictates both mood and strategy, one of golf’s most distinctive tournaments has unfolded for nearly nine decades. Known originally as the “Crosby Clambake” and today as the AT&T Pebble Beach Pro-Am, the event occupies a singular place in professional golf — where competition, celebrity, philanthropy, and natural beauty intersect in a way no other tournament quite replicates.

What began in 1937 as an informal gathering conceived by a superstar entertainer, Bing Crosby, has evolved into a PGA TOUR Signature Event, drawing the game’s elite while preserving the spirit of camaraderie that defined its earliest years. The tournament’s longevity and character are inseparable from its setting: the Monterey Peninsula, home to some of the most celebrated golf courses in the world.

–

Bing Crosby with Bob Hope and Frank Sinatra at a promo shoot, 1944

–

Bing Crosby and the Birth of a Tradition

Harry Lillis “Bing” Crosby Jr. was one of the most dominant entertainment figures of the 1930s and 40s. He achieved unprecedented success as a recording artist, radio star and Hollywood leading man during the formative years of mass media. His relaxed vocal style revolutionized popular singing, while his box-office appeal and hit records made him one of the first true multimedia superstars of the twentieth century.

When he launched his eponymous “clambake” golf get-together, Crosby was not merely a celebrity host lending his name to a tournament; he was an accomplished golfer with a deep affection for the game. A low-handicap amateur, “Der Bingle” believed golf was best enjoyed as a social experience—competitive, yes, but enriched by conversation, laughter, and shared meals.

In 1937, at Rancho Santa Fe Golf Club near San Diego, Crosby invited a small group of professional golfers and Hollywood friends for a one-day pro-am. After the round, participants gathered for a seaside clambake. The combination of golf, food, and celebrity fellowship immediately struck a chord. Sam Snead won the professional competition, earning $500, and the Crosby Clambake was born.

The event quickly became an annual fixture, though World War II interrupted its run. When it returned in 1947, Crosby made a pivotal decision that would define the tournament’s future: he moved it north to the Monterey Peninsula. With that relocation, the Clambake found its permanent identity — and its perfect stage.

–

The Monterey Peninsula: A Natural Fit

Few places in golf possess the mythic appeal of Monterey. Its rugged coastline, ever-shifting light, and natural contours created world-class golf courses that challenge the best of players. For Crosby, the region offered even more: an atmosphere that encouraged fellowship while demanding excellence.

Weather has often been a silent protagonist. February storms, swirling winds, and cold rain have shaped outcomes and added drama—particularly at Pebble Beach, where conditions can transform a benign hole into a formidable test within minutes.

The tournament rotated among several courses in its early Monterey years, including Pebble Beach Golf Links, Cypress Point Club, and Monterey Peninsula Country Club. Over time, Pebble Beach emerged as its centerpiece.

–

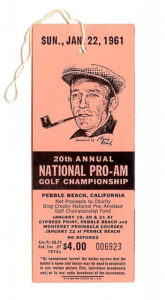

The “Crosby Clambake” Era

For nearly five decades, the tournament was officially known as the Bing Crosby National Pro-Amateur, though fans and players alike preferred its informal nickname. The “Clambake” became one of golf’s great social institutions. Movie stars, musicians, athletes, and business leaders teed it up alongside the game’s top pros.

–

–

The format was relaxed by modern standards, and the atmosphere often felt more like a gathering of friends than a stop on a professional tour. Crosby himself was omnipresent: hosting dinners, greeting players, and reinforcing the tournament’s ethos that golf should be fun, inclusive, and generous in spirit.

Yet beneath the casual exterior, serious golf was being played. Over time, the event adopted a full 72-hole format and became firmly embedded on the PGA TOUR schedule. By the 1960s and 1970s, winning the Crosby carried genuine prestige.

Crosby remained the tournament’s guiding force until his death in 1977. Though the “Clambake” would eventually change names, his influence remains embedded in its DNA.

–

A New Era: Corporate Sponsorship and Evolution

By the mid-1980s, professional golf had entered a new commercial reality. In 1986, AT&T became the title sponsor, and the tournament was rebranded as the AT&T Pebble Beach National Pro-Am. The change marked a shift toward larger purses, expanded television coverage, and a stronger emphasis on elite professional competition. Yet unlike many tournaments that lost their personality during the corporate era, Pebble Beach retained its charm. The pro-am format endured, as did the tradition of pairing professionals with amateur partners — now a blend of celebrities, executives, and philanthropists.

In recent years, the PGA TOUR elevated the event to Signature Event status, ensuring elite fields and heightened competitive significance. The modern tournament balances its original spirit with the demands of contemporary professional golf.

–

The Courses at the Heart of the Story

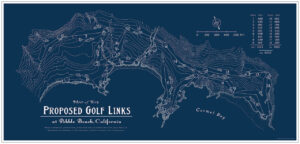

No course is more central to the tournament — and one of the most iconic in the game of golf — than Pebble Beach Golf Links. Samuel F.B. Morse, a distant cousin of the inventor of the Morse Code, founded what would become the Pebble Beach Company in 1919. Affectionately known as “The Duke of Del Monte,” Morse was its faithful steward for the next 50 years. His vision was to keep the Pebble Beach coastline open for public enjoyment and he gave architects Jack Neville and Douglas Grant sufficient land to locate nine holes overlooking the Pacific Ocean along Stillwater Cove and Carmel Bay.

–

Samuel F.B. Morse

–

As golf course architects, Neville and Grant were neophytes. But both were accomplished golfers. When he was asked to build Pebble Beach, Jack Neville was a two-time past champion of the California State Amateur Championship. Neville won the inaugural event in 1912 at the age of 20, and would go on to win a record five times. Douglas Grant had won the 1908 Pacific Coast Championship, the 1916 Western Amateur at Del Monte, and the California Amateur in 1918. The two applied their golfing skills and insights in developing plans for the new links at Pebble Beach. The brilliant success of their work is undeniable, resulting in a dramatic routing where the Pacific influences club selection, psychology, and aesthetics.

–

Original plan of Pebble Beach Golf Links

–

Pebble Beach’s strategic depth has been refined by several architects over the decades, including H. Chandler Egan, Alister MacKenzie, Jack Nicklaus and Arnold Palmer. Each redesign has added modern challenge without disturbing the course’s character. Television has made its iconic holes along the ocean familiar, especially the stunning, short par-3 7th hole with its tiny green on a rocky point, the challenging cliffside par-4 8th hole requiring a heroic second shot over a chasm, and the spectacular, risk-reward par-5 18th hole, one of golf’s greatest finishing holes.

–

Pebble Beach’s par-4 8th hole

–

If Pebble Beach is poetry, Spyglass Hill Golf Course is prose — direct, demanding, and unsentimental. Dating to 1966 and designed by Robert Trent Jones Sr., Spyglass opens with seaside holes through dunes before turning inland into dense forest. The contrast is striking, and the challenge unrelenting. Jones considered Spyglass one of his finest designs, and many professionals regard it as the most difficult course used in the Pro-Am rotation. Long par-4s, elevated greens, and narrow corridors reward discipline and punish indecision.

Speaking of prose, Edinburgh-born writer, Robert Louis Stevenson, wasn’t a golfer of any renown but his literary work, particularly Treasure Island, deeply influenced the naming and theme of Spyglass Hill.

Stevenson lived in the Monterrey area in 1879 and he often traversed the dunes that became Spyglass Hill. Local lore holds that this seaside location was “his muse for the buccaneers and buried gold” in that classic tale. The names of the course and the vast majority of its holes were named after the novel’s characters and places.

It begins with the par-5 first hole that stretches to nearly 600 yards, named Treasure Island. Its green is quite literally an island placed in a sea of sand. It’s said that the quest for buried treasure (not to mention pars and birdies) begins here. Another par-5, the 14th hole, is named Long John Silver, for the novel’s principal antagonist, a cunning, peg-legged pirate. The 18th hole is Spyglass. That’s the name of the largest hill on Treasure Island. Spy-Glass is also the name of Long John’s tavern.

–

Spyglass Hill’s par-3 3rd hole: Black Spot (a dreaded pirate summons in Treasure Island)

–

Monterey Peninsula Country Club (MPCC) played a formative role in the tournament’s early Monterey years. With two distinct courses, the Shore and the Dunes, MPCC offered variety and flexibility during the Clambake’s formative decades. While it no longer plays a primary role in the modern event, MPCC’s history is woven into the tournament’s identity. The Dunes course hosted the event from 1947 to 1964. The Shore course hosted in 1965, 1966, and 1977, and in 2010, the Shore course returned to the event’s rotation.

Under Morse’s leadership, Monterey Peninsula Country Club opened in 1926. The club’s signature Dunes Course was originally routed by East Coast architect Seth Raynor in 1924. After Raynor’s death in 1926, Robert Hunter completed the design, and several designers have made subsequent renovations to improve its playability and aesthetic qualities.

MPCC’s Shore Course was developed in the early 1960s based on a design by Bob E. Baldock and Jack Neville. It underwent a celebrated redesign by Mike Strantz in 2003, who was battling cancer at the time, that dramatically enhanced its strategic and scenic qualities. Strantz reversed the direction of the fifth through 15th holes to provide a Pacific Ocean backdrop to most of them. He weaved fairways among trees so players could “dance among the cypress,” and added native grasses for a coastal prairie look. The stunning landscape would be Strantz’s last work. He died six months after completing the redesign. Designer Dave Zinkand completed a renovation of the bunkers in 2025 “in the spirit of Strantz.”

–

Past Champions: Top Professionals in Each Generation

Over the decades, the tournament has crowned champions who reflect every era of professional golf. From its earliest years, its champions have included Hall of Fame legends such as Sam Snead (1937), Ben Hogan (1946), Byron Nelson (1947), Jimmy Demaret (1948), Cary Middlecoff (1955), and Jack Burke Jr.

(1956). Snead won this event four times.

In the modern era, its champions have also been among the world’s best players. Only thirteen players won this tournament more than once. Mark O’Meara and Phil Mickelson won five times. Three-time winners are Jack Nicklaus and Johnny Miller.

–

Jack Nicklaus playing hole #8 at the 1993 AT&T Pebble Beach Pro-Am

Four players have won this event and a U.S. Open at Pebble Beach: Nicklaus, Tom Watson, Tom Kite and Tiger Woods. Woods accomplished that feat in the same year (2000).

–

Last year, Rory McIlroy’s victory illustrated the tournament’s continued relevance at the highest level of professional golf. He combined modern power with disciplined course management. It showed that while equipment and athleticism have evolved, Pebble Beach still rewards thoughtful, strategic play.

Rory McIlroy, 2025 AT&T Pebble Beach Pro-Am champion

–

Why the “Crosby Clambake” Still Matters

–

One of the tournament’s most enduring legacies is its philanthropic mission. From its earliest days — and long before it became a common practice at PGA TOUR events, the “Crosby Clambake” raised funds for charitable causes. This commitment continues to this day, reflecting Bing Crosby’s original vision: that golf, at its best, serves not only players and spectators, but communities as well.

In an era of hyper-professionalized sports, the AT&T Pebble Beach Pro-Am stands apart. Celebrities still walk the fairways, amateurs still share moments with professionals, and the Pacific still exerts its quiet authority over shotmaking.

The tournament endures because it has never abandoned its founding principles. The name has changed but its essence remains: great golf, remarkable scenery, shared experience, and generosity of spirit.

From a casual clambake organized by a Hollywood star to one of the PGA TOUR’s most distinguished events, the tournament’s mirrors the evolution of professional golf. Few events can claim such a seamless blend of history, place, and purpose. Fewer still can do so while remaining unmistakably themselves, an enduring achievement of the “Crosby Clambake.”